On Worldbuilding and Ursula K. Le Guin

Hello dear readers, and thank you for checking in for another bimonthly dev log ~<3

Before we get started on the main topic for today, I'd like to let everyone know that due to an evolving personal matter concerning a member of our team, we've had to re-evaluate our workflow.

We've been very conscious of the impact committing to a large project like The Inverted Spire can have on health and work-life balance from the very beginning. Whether that's in the form of detailed content warnings for beta readers, or making sure our team members don't over-commit at the cost of their own wellbeing, we want to continue making that promise a reality. In this case, it means changing some dates to make sure nobody's health is compromised by working on the project.

Upon discussion, we decided the best way to handle this was:

1- Push our beta reader feedback dates to the month of October (official start date now September 30th)

2- Push the full release for Chapters 1 & 2 to November 30th.

As a byproduct of this decision, we will also still be accepting new beta readers all the way until September 28th (so if you're still interested, but thought you missed the deadline, you can check out our call here).

While the date change is unfortunate, we feel that ultimately, the health of our team members comes first.

We also believe that the more sustainable our production schedule remains, the better our final product becomes!

Now on to the dev log itself~

In our last dev log, we talked about the relationship between theatre, the courtroom drama, and visual novels as an evolving medium.

While the storytelling language of theatre may be the primary mover behind a lot of our decisions around staging and game mechanics, when it comes to worldbuilding, we're coming from a very different place.

As we hinted earlier, The Inverted Spire is at home with a pretty broad and eclectic frame of literary reference. It falls into the evolving tradition of fantasy sub-genres responding to (and arguably pushing back against) the 20th century canon that romanticizes pseudo-historical pastoral settings (often based on medieval Western Europe), and retells the legendary hero's journey into oblivion a thousand different ways. There are many parallels to be drawn with the New Weird genre, Soviet (and post-Soviet) fantastika, and other forms of postmodernist speculative fiction.

But today I'd like to talk about what is perhaps the most obvious and direct literary influence on the world of The Inverted Spire:

Ursula K. Leguin's The Left Hand of Darkness.

Both And One, oil on panel, 16×12″ Interior illustration by Vaness Lamen for an Illustrated Limited Edition ot the book through Easton Press / MBI, Inc.

For those of you who are less familiar with it, The Left Hand of Darkness is an immensely popular science fiction novel. It revolves around the diplomatic efforts of a Terran native, making first contact with the planet Gethen to convince its residents of joining an interplanetary alliance of humanoid worlds.

A pretty common premise on the face of it!

Until you realize the inhabitants of Gethen are androgynous, ambisexual beings embroiled in a multi-tier international political conflict of their own, and our protagonist is about to become one of many moving parts at the center of their evolving intrigue.

This novel was my first encounter with themes of gender and sexuality taking the wheel in a work of genre fiction. It's an especially daring concept when you consider that it was first published in 1969!

Unfortunately, the publication date is reflected in some of the author's creative choices. As much as I will always love this novel, it's hard not to question why the genderless Gethens all use male pronouns, and are depicted almost exclusively in traditionally masculine gender roles. How are essential topics that form the backbone of any society—topics like child-rearing, caretaking and housekeeping—addressed by the Gethens at all? Aside from a handful of brief anecdotes, we never really find out And as for their sexuality—why is it that heterosexuality, along with all the baggage of its traditional gendered norms, suddenly becomes default in the beds of a genderless world?

Photo from a theatre adaption of The Left Hand of Darkness by Portland Playhouse and Hand2Mouth Theatre, with Julie Hammond (left) as Estraven and Damian Thompson (right) as Genly Ai.

Perhaps the best illustration of the author's ongoing battle with the core premise of her own worldbuilding lies in the following passage, where Genly Ai, who is implied to be a straight, cisgender man, struggles to wrap his head around his host, the Gethen prime minister Estraven:

"Thus as I sipped my smoking sour beer I thought that at table Estraven’s performance had been womanly, all charm and tact and lack of substance, specious and adroit. Was it in fact perhaps this soft supple femininity that I disliked and distrusted in him? For it was impossible to think of him as a woman, that dark, ironic, powerful presence near me in the firelit darkness, and yet whenever I thought of him as a man I felt a sense of falseness, of imposture: in him, or in my own attitude towards him? His voice was soft and rather resonant but not deep, scarcely a man’s voice, but scarcely a woman’s voice either…but what was it saying?"

Now, Genly does eventually manage to overcome some of his Terran assumptions about gender (and women in particular) to see Estraven as a fully-realized person. But his biased perspective lends the entire story an aftertaste as sour as Gethen beer (in the humble opinion of yours truly).

It's hard not to read this passage as someone who exists on the opposite side of the page—more of an Estraven than a Genly—and not see the protagonist's words mirrored in my own real-world experiences with uncomprehending others. Harder to still to sit with the fact that Genly is the protagonist of this story (rather than the far more interesting Estraven) precisely because his ideas about the world are presumed to be the real-world default of its audience. The funny result is that I have a sort of out-of-body experience whenever I come back to Left Hand, and find myself immersed in a thoroughly straight, cisgender point-of-view—looking back on myself as an alien lifeform from the planet Gethen.

Of course, I am far from the first reader to raise these questions.

LeGuin would spend many decades responding to criticism of the novel, and at times, amending her views, or else expressing regret for assumptions she no longer agreed with. She even published new stories (such as Coming of Age in Karhide in 1995), which effectively retconned some of the more outdated ideas in Left Hand, though many of its deeper gendered premises remained untouched.

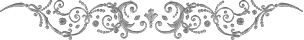

Estraven (left) and Genly Ai (right) on a dangerous eighty-day trek across the northern Gobrin ice sheet back to Karhide. Illustrated by David Lupton for a Folio Society publication of Ursula K. Le Guin's novel.

One of the questions LeGuin would have the hardest time responding to (judging by how many times she changed her answer) is why?

Why tell a story about a genderless world?

The implication of this question is of course that our world is gendered. Irrevocably, essentially gendered. So if you're telling a story set in a place with no men or women, surely you must (ironically) be making some kind of point about men and women?

The idea that a conscious real-world perspective might exist outside, or perhaps between these two dualities is relegated to the world of aliens, gods and monsters.

Now, I'm not going to flatter myself by claiming The Inverted Spire is some kind of attempt to perfect the world that LeGuin so masterfully constructed (for all its debated failings).

The truth of the matter is more complicated. Because what I saw in Left Hand was the the reflection of a possibility. An open door, inviting the many underwritten perspectives already brimming in my head into the blank textbox on my laptop screen.

It was Left Hand that left me with the unshakeable belief that we no longer need a Genly Ai to be our lens into Estraven's world. And further, that the existence of such a world no longer needs to be justified as a commentary on men and women. It simply is, as Estraven simply is, despite all of Genly attempts to project his notions of gender onto that "dark, ironic, powerful presence" sitting "in the firelit darkness."

Wraparound cover art (back and front) by Tim White from an edition of The Left Hand of Darkness with Futura, 1981

But how is the absence of gender actually relevant to the worldbuilding of The Inverted Spire? What does it change? Is it really important at all?

Why yes, dear reader, I would argue it is and does!

In the first place, it sets up a world where roles fundamental to a functioning society entirely lack a gendered component. There is no concept of motherhood or fatherhood, with their own distinctive traditional properties. In fact, reproduction itself is an entirely genderless process, where either partner can choose to be either the carrier of a child, or the donor of genetic material. Any individual goblin may alternate between these two roles throughout their life, and there are no significant assumptions attached to either.

In Old Order, this generated clans united by a complex series of blood ties that were more akin to a constellation chart than a family tree. Goblins were always raised in a community setting, rather than a nuclear family. But New Order introduces even more stringent restrictions on family bonds in order to escape the clutches of Old Order nepotism.

Most New Order goblins have no idea who their biological parents are, having been passed from one community home to another, and one series of assigned mentors to another, all throughout their lives.

Instead of allegiance to a family, goblins tend to have fealty with their magical discipline, and the corresponding Guild that fosters it. They are encouraged to produce the next generation of goblins by the promise of advancement within the Guild itself. Though some goblins are predisposed to be nurturing, and actively seek out mentorship roles, most goblins will at some point be assigned apprentice graduates out of academies on principle.

The academies themselves, as a byproduct of the age of casting, are generalist schools where full-time mentors from an assortment of magical disciplines prepare and evaluate young goblins for an eventual Guild assignment.

All goblins (aside from those licensed for travelling professions) live in communal dwellings mixing various disciplines under one roof. Older residents in these domestic arrangements are occasionally nominated as 'guardians' for new arrivals of academy age. They are loosely held responsible for mentor-like obligations in all realms outside of formal academy training. Typically, a single underage goblin is assigned three or four guardians at once, so they can share these responsibilities amongst themselves.

Screenshots from the new release (top) and original prototype (bottom) depicting the protagonist of The Inverted Spire writing their last entry into an official Bureau of Service journal.

Goblin romance, while very much real, carries no expectations of lifelong attachment akin to marriage. In fact, there is no equivalent to the concept of marriage in TIS. While individual goblins may choose to have life partners, expectations of monogamous commitment simply do not exist in their world. This certainly doesn't mean an absence of the concept of jealousy, but it lacks a moral weight. Goblins are jealous simply because they are emotional beings that crave respect, companionship and affection, and not in association with any relationship-related duty.

Gendered power dynamics and behaviours don't exist in the goblin world, but assumptions based on Guild and creed are abundant. The rarer the magical discipline, the more likely it is to be mired in stereotypes and hearsay. Power is likewise distributed among different 'circles' within a Guild, with Guildmasters and Council representatives at the very top of the hierarchy. Even between Guilds, those with greater numbers like the Artificers, or the ones with rare powers, like the Mentalists, indisputably hold greater sway within the Council itself.

And finally, within New Order, there is the matter of Equation scores, and the sprawling bureaucracy of the Bureau of Service. The higher a goblin's Equation score, the more access they have to better living conditions, greater comforts, and higher Guild positions.

In short, the goblins of New Order don't lack a concept of gender or gender-based sexuality because they're talking puppets for some kind of Gender Studies 101. They simply begin with a point-of-view different from someone who does filter their behaviour through a naturally assumed familiarity with manhood or womanhood. This makes their reflections on the troubles that do plague their nation, and even the nature of their own alleged crimes, significantly different from someone coming from a world where binary gender is the default.

But it makes those troubles no less real—and certainly no less darkly familiar.

The need for love. A sense of purpose. A sense of personal identity. Existential dread and despair. These are all things that goblins know well. And they are all things that the story of TIS explores in exhaustive detail.

So what's next?

Our next dev log is coming up on September 30th. Is there any topic in particular that you'd like us to cover?

We'd also love to hear your thoughts~ whether its on the the notion of a genderless world, LeGuin's novels (and other speculative fiction) or other topics related to fantasy worldbuilding.

And if you're curious to read more about the writing process for TIS, I have another (rather timely) journal entry on "writing nuanced depictions of people who do bad things" which you can have a look at here.

Your thoughts and comments are as welcome as ever. ~<3

Get The Inverted Spire

The Inverted Spire

Goblin mages dungeoncrawl to redemption.

| Status | In development |

| Authors | N. A. Melamed, feardeer, Mickey Hoz |

| Genre | Visual Novel, Interactive Fiction |

| Tags | Amare, Dark Fantasy, Dystopian, Horror, LGBT, Meaningful Choices, Mystery, Romance, Story Rich |

| Languages | English |

| Accessibility | Color-blind friendly, High-contrast |

More posts

- Progress, Deep Lore and Significant DetoursJul 14, 2023

- Game Updates and the Shadow of WarMar 15, 2022

- Love among the Damned: On Romance in the Inverted SpireFeb 15, 2022

- Goblin Fashion and Sexy Drug Gloves: On Clothing as Worldbuilding in The Inverte...Jan 19, 2022

- 2022, Here we come~Dec 31, 2021

- New Release available for download!Dec 01, 2021

- On What We're Learning from Working with our Beta ReadersOct 15, 2021

- On Painting Facial Expressions and a New Team Member!Oct 04, 2021

- Visual Novels as Theatre & Other Storytelling InspirationsAug 31, 2021

Leave a comment

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.